I gave a talk today called Internet of Nothings: Technology and Our Relationship With the Things in Our World at LXJS, a JavaScript conference in Lisbon, Portugal. I’m excited to have been given the opportunity to talk about the philosophy of technology! There’s an embedded video of the talk below, and I’ve included the slides, the slightly-edited text of my notes, as well as the lyrics to the song I performed. If you’re new to my blog and this topic, I recommend checking out my Blogging Borgmann series, where I’m blogging chapter-by-chapter through a book on the philosophy of technology by Albert Borgmann. Enjoy!

Talk video

Thanks to @aca_video for the video!

Slides

Talk notes/transcript

Hello everyone! Good morning! I’m Jonathan Lipps, @jlipps on Twitter, and I work for a company called Sauce Labs. I’m in charge of our Ecosystem & Integrations team, which means I help take care of the open-source ecosystem around Sauce Labs and automated testing. Mostly I work on a project called Appium, which I talked about at LXJS last year. I’m really proud that Sauce is sponsoring LXJS again! And I want to thank the organizers for the amazing job they’ve done making this a remarkable conference for the JavaScript community. Last year, with their support and encouragement, I had the most fun I’ve ever had giving a conference talk, and I’m very thankful to have the opportunity to hang out with you guys a second time.

This year, I don’t have a crazy software robot music demo. Instead, I want to engage you guys with some questions I think are important for us to wrestle with. Something I love about the JavaScript community is that we take the time to talk about more than programming. We don’t always have a perfect dialogue about cultural issues, but I’m heartened that it exists. There are many industries out there you’d be hard-pressed to find the barest recognition that its community is made up of people, not just “professionals”. I like that the JavaScript community, and this conference, recognize that we are human beings first and foremost, even though we are gathered here because of a shared love for programming and JavaScript. So here’s my attempt to engage that human aspect of our technological adventure.

I think what I have to say is best digested as a conversation, not a series of bullet points, and I want these 20 − 30 minutes to be merely the first words of that conversation. I hope you’ll listen to what I have to say, evaluate it critically, and find me sometime this weekend to continue the dialogue.

OK! Enough preamble. I want to talk to you guys about the philosophy of technology. Philosophy and technology are both long-term loves of mine, but it’s only recently that I was made aware that you could put them together. Of the two, technology came first for me. Let’s take JavaScript specifically since we’re at LXJS: I wrote my first JavaScript code about 17 years ago when I needed a scrolling ticker for a welcome message on my website. Sounds like exactly the sort of thing you’d use JavaScript for back then, right? And when I say “wrote”, I mean, “copy and pasted”. It wasn’t until 12 years ago that I wrote my first JavaScript program from scratch myself—a supremely customizable, JS-only drop-down menu script. I even made it “open-source”, though I had no idea what that really meant!

When I got to university, instead of studying computer science as I originally intended, I chose to pursue philosophy, because I was curious about the biggest questions it was possible to ask: questions about God, the nature of reality, the nature of science, how we truly know things, and so on. Of course, there’s not a lot of job opportunities as a philosopher, so I ended up becoming a programmer by trade anyway.

One thing I learned from philosophy is how to approach questions. Another thing I learned, which any of you who’ve had a philosophy course can corroborate, is that there are always more questions to ask. It can start to feel disorienting, when you’ve asked so many questions, like the rabbit hole goes on forever, and we might as well get back to doing Real Work (like programming, maybe).

Sometimes, this otherwise praiseworthy pragmatism can leave important issues unexamined. And as we know from Socrates, “the unexamined life is not worth living”. So, what have we left unexamined in the pursuit of our technological careers? What has the world left unexamined in its wholehearted and wholesale adoption of technological solutions to nearly every problem? Quite a lot, I’d argue! But now I just want to focus on two areas of modern technology, two buzzwords which are familiar to us in our community: the first is the Internet of Things, and the second is the Quantified Self.

What is the Internet of Things? In my understanding it’s the concept that everyday objects, things which have not traditionally been considered computers, can and should be connected to each other, networked in order to enhance the benefits they provide. Another way of looking at it is to say it’s the process of turning “things” into “devices”.

Now’s a good time to introduce my favorite philosopher of technology, a professor at the University of Montana, Albert Borgmann. Part of Albert Borgmann’s take on on technology is that there is a deep and significant divide between “Things” (Capital-T), and “devices”. This distinction is so important that for him, that for him, technology itself is characterized by what he calls the Device Paradigm. I’ll explain the Device Paradigm in a moment.

A central question in the philosophy of technology is whether technology should primarily be thought of as a content-less tool, which gains significance purely through the intentions we as the tool-users give it, or whether it has a character of its own, independent of how it is intended to be used. In other words, is technology more like an axe—a tool which can be used for the beneficial purpose of chopping firewood, or the horrible purpose of murder—or more like capitalism or socialism—systems which shape and color every action that takes place within their paradigms, no matter the intent behind those actions? Most people like to think of technology as a tool. We can appropriate it for good purposes or bad, but technology itself is neutral; it has no character outside of the purposes we put it to. But Albert Borgmann has a strong argument that this isn’t the right way to look at technology, and it involves the Device Paradigm that I mentioned earlier. Borgmann claims that technology can best be understood and explained by looking at canonical examples (i.e., a “paradigm”), and noting what they have in common.

What they have in common is the attempt to make a certain good available in a non-burdensome way. What I mean by “good” in this case is just something that’s necessary or desirable for human life. Food, drink, safety, entertainment, etc… And what I mean by “available in a non-burdensome way” can be cashed out in terms of four requirements. Let’s take an example to explore these requirements more concretely. Let’s say the good is heat. For many parts of the world, some form of non-naturally-occurring heat is an essential part of daily existence, especially in winter. Now we can think about different ways of procuring this good of “heat”. A pre-technological way would be to light a wood fire in a stove, whereas a technological example is the kind of electric- or gas-powered central heating systems most of us probably have in our homes.

It’s probably obvious that a fire is not available in a non-burdensome way, when compared with a central heating system. But let’s go through the four aspects of “availability” to see why. For something to be truly “available” in this sense is for it to be, first of all, instantaneous. A wood fire is definitely not instantaneous. Wood is not instantly available in burnable form; it has to be chopped and gathered, which is a hard and time-consuming process. A central heating system, on the other hand, begins to provide heat as soon as you flip a switch or move a dial.

Secondly, perfect availability requires that a good be ubiquitous, meaning it must be available everywhere. A wood fire does not meet the standard here, in that when it provides heat, it does so unevenly, only in the vicinity of the fire itself. A central heating system uses a combination of ducts and vents in order to ensure that the entire house benefits equally from the heat.

The third requirement is safety. For a good to be perfectly available, it must be provided in a perfectly safe way. A wood-burning stove is definitely not safe. Working with the tools required to chop wood can be a source of serious accidents. And the fire itself of course is very dangerous, potentially causing death and destruction if not tended appropriately. A central heating system, on the other hand, is relatively safe. We can leave it on for months or years without worrying that it will burn down our house.

Finally, for a good to be truly available it must be delivered easily, without a lot of physical or cognitive effort. It definitely takes a lot of effort to prepare, use, and clean a wood-burning stove, never mind the effort to chop and stack the wood in the first place. It takes mental effort to remember to check the stove and keep it heating optimally. Central heating, on the other hand, is so easy to use, many of us forget that it’s even a part of the house. We can set it on a program that matches our heating needs and not think about it ever again, unless it breaks down.

So, this is the foundation of the Device Paradigm: the process of making goods available in a non-burdensome way. And indeed, this has been precisely the promise of technology since Descartes dreamed about what control of the physical environment would allow humanity to achieve—the elimination of the burdens and dangers that made life disagreeable and unpleasant. This sounds like a reasonable, laudable goal, right? I won’t argue that it’s not. But it’s important to realize two things about it. First of all, this is the very DNA of technology. It’s a philosophical stance at the very core of the technological enterprise. Everything technology touches is going to be shaped according to this philosophy. In that sense, it’s not true that technology is just a neutral tool. It has a definite character, and that character is the continuous attempt to make goods available in a non-burdensome way.

Secondly, and more importantly, this focus on availability leads inevitably to a rift down the middle of things themselves, a division of a thing into a mechanism and a product. Let’s go back to the example of heating. In pre-technological eras, it wasn’t possible to distinguish a good from the way that good was procured. In the middle of a cold winter, it wasn’t possible to have heat without fire. And it wasn’t possible to have fire without firewood. And it wasn’t possible to gather that firewood without going through the laborious process of chopping up trees. So staying warm was inextricably tied up with this direct physical investment of time and energy.

But once we have enough control of nature, we can produce heat without firewood. We can begin to think of heat as a commodity, as something independent of the way that it is produced. And once we do this, we can begin to care progressively less about the way that it is produced, until we wind up with the current situation, where we enjoy central heating in our homes without having any idea how it actually works. And it doesn’t matter. If central heating technology changed tomorrow to use a completely different method of heat production, and someone installed it in our house without telling us, we would never notice. What matters to us is the commodity, the good that is produced.

Let’s look at another common device as an example: a television. What is the good or commodity that a television provides for us? Well, embedded in a larger cultural system, it’s entertainment or information. But purely as a physical object, the good that it produces is clarity of representation of a moving picture. What we would predict then, on the basis of the Device Paradigm, is that the physical construction of a TV might change radically over the years, while the screen—the part that is most directly related to providing the good (clear representation of a moving picture)—would change in basically one way: becoming even clearer and more prominent. And this is exactly what we find. Early TVs were mostly bulk, with a small, distorted, black-and-white screen. And through a variety of vastly different picture-producing mechanisms, we have gradually evolved to where we are today: Large, flat TVs where it is almost not possible to see anything other than the amazingly-clear screen. We don’t care that our TV set uses liquid crystals rather than vacuum tubes, and if the technology changed tomorrow to something cheaper or easier to manufacture, hardly anyone would even notice.

The point that I’ve been trying to make is that devices don’t have a single essence. They have a divided essence: two aspects, or layers. One aspect is the thing the device does for us: its commodity, good, or function. The other aspect is the physical stuff of the device itself: the arrangement of silicon and metal, or whatever, that enables the device to live out its function. Another way of looking at it is that there’s a distinction between means and ends in devices themselves. What the device is for, and how it does what it’s for. This all might seem obvious and natural to us, given that our world is full of devices. But this distinction, this way of looking at things, is actually radically new in the history of humanity. In the pre-technological era, you couldn’t have heat without a stove or fireplace in your room. You couldn’t have music without a musician and an instrument. You couldn’t enjoy a dramatic performance without the actors there in front of you.

OK, so what? What’s wrong with making the ugly parts of a TV less prominent, and the screen more prominent? And the answer is: nothing. Nothing’s wrong with it. The sole purpose of a TV is to provide a full, clear picture, and so the ideal TV is pure picture and nothing else. The problem comes in when we use technology to make goods available to us which were once delivered through a deep engagement with the natural world or society, and which often brought along intangible or unquantifiable goods with them as part of the process. Let’s go back to the example of the wood-burning stove. It certainly had all the drawbacks that I mentioned before in terms of availability. Compared to a central heating system, chopping wood and keeping it burning in one room of the house is an awful lot of wasted energy and work. But along with the tedium came some benefits. Gathering and chopping wood served as part of the daily rhythm that oriented, that served as a reference point for the rest of the day’s activities. The fact that the heat from the stove was available in only one room of the house meant that the entire family or community would gather in one place for the evening, would experience together whatever that evening held, whether it was reading, music, or discussion.

Or let’s take another example, that of food. Food is certainly a good that we would like to be more available in the sense I talked about before, and indeed we can make it technologically available to our societies. A frozen TV dinner is probably the easiest example to think about. The promise of a frozen TV dinner is to deliver the twin goods of nutrition and a flavor reminiscent of an actual freshly-prepared meal, but without the inconvenience of growing, harvesting, and cooking the food yourself. It is food turned into a device, instantly available. But of course for most of human history, enjoying the good of a meal was inextricably linked to engagement with the earth through farming, engagement with the community, engagement with the tradition of the culinary arts, and finally celebration and conversation with the others who were also at the table. For the sake of availability, these less quantifiable goods have been replaced by the technological mechanisms that make it possible for TV dinners to exist—industrial agriculture, chemistry, food science, etc…

Through technological innovations like central heating and instant food, we have figured out a way to deliver to ourselves what we thought we always wanted in terms of the goods of heat and food, but as a result of them becoming technological devices, we have ripped them free of the things and practices that used to be necessary for us to enjoy them. And it turns out that some of these things and practices, like manual labor, engagement with and knowledge of the natural world, the skill of cooking, or the celebration of a community, are really important for us as humans.

This isn’t the fault of technology, as if technology were some person out there trying to destroy human significance. But the Device Paradigm encourages us to think more and more in terms of means and ends rather than unified wholes, more and more in terms of devices rather than things, more and more in terms of quantifiable commodities rather than qualitative or unquantifiable goods, and more and more in terms of individual consumption rather than collective creativity.

So let me bring it back to the Internet of Things. Am I saying that the things in our lives shouldn’t be more connected, that we should stop writing JavaScript to control physical hardware, otherwise we’ll ruin society? No! I’m simply trying to get us to recognize that the driving force of technology, the Device Paradigm, entirely ignores the hard-to-define unquantifiable goods that make up human significance. I want us to ask a few questions before we wave our magic technology wand over something that looks like a problem, to make sure that in solving it, we’re doing so in such a way that leaves us just as human as we were before.

Speaking of being human, let’s talk for a minute about the Quantified Self. The technologist Jaron Lanier has a great book called You Are Not a Gadget that I think addresses this topic in a much better way than I can. All I want to say is that I fear the Quantified Self movement will lead to treating human beings as devices rather than persons, rather things in ourselves, and, historically, treating humans as anything other than persons has disastrous consequences. Don’t get me wrong; I love data as much as the next nerd, and I was initially inclined to jump on board this bandwagon. Track my runs so I can create reference points and understand my progress? Track my sleep so I can adjust my life to get better quality rest? Absolutely! And I think these things really are positive. The danger here is that it encourages us to think of ourselves in terms of statistics, in terms of quantifiable information that can be neatly categorized, filtered, and sorted. But we’re not like that. And it encourages us to think of others in that way as well, opening up infinite opportunity for unhelpful and meaningless comparison.

We “quantify” ourselves for the sake of software these days in a lot more ways than tracking our bio metrics. Every time we select a choice from a select box on a social networking site, we’re choosing to present a squared-off, low-fidelity version of ourselves. I don’t need to tell you that the common task of choosing a gender from a select box can be an extremely self-limiting experience for many people. But computer programs ask us to circumscribe ourselves in many more subtle ways. Just because it’s convenient for computers to think in terms of binary or mutually exclusive categories, just because it’s convenient for database queries to filter based on pre-set options, doesn’t mean this is a good way to model human identity or relationship. But humans are really good at adapting, and we’ve been really good at adapting to what has been technologically feasible or technologically easy. The result is that we have grown more like computers in our self-understanding and self-description, rather than the other way around. Did it have to be that way? No, I don’t think so. I have hope that once we stop lowering our standards to deal with computers, we’ll develop apps that we’ve put a lot more humanity into, so we can remain human while using them.

OK. In wrapping up this part of my talk, I want to reiterate that I am a technologist. From the time I was young I was impressed by the power of technology to change the world, and the possibilities for creative expression it opens up, and I still am. I loved writing code to play music on mobile devices last year! I’m not trying to get you guys to stop hacking on connected devices or social networks. What I’m trying to do is to get this community to start looking at technology, not just as a tool, not just as the obvious solution to the world’s problems, but almost as an entity in its own right, that has its own characteristic way of operating. We need to know ourselves before we engage with technology, or we will find ourselves and our creations unwittingly reshaped by it. We need to decide for ourselves what it means to live well as a human being. This is one of the classic questions of philosophy: what is the good life? I’m certainly not going to talk more about it here! I gave some hints along the way of what I think might be involved, and I’d love to engage you all in further conversation about it, but the point is that we need to go down that rabbit hole for at least a little bit if we want to answer the questions I raised about how we go about developing technologies that augment and ennoble human persons, rather than diminishing and demeaning ourselves and our neighbors.

I wanted to leave you with a concrete experience to accompany the very philosophical nature of this talk. The most symbolic thing I could think of to do was to play a new song for you guys. It’s a song I wrote with the theme of this talk in mind. I wanted to capture the idea that there is something unique about a shared physical experience, especially when it comes to music. Maybe in the future I’ll record this song, and through a number of takes maybe I’ll capture a “perfect” performance. But I think the minor variations and even missed notes in a live performance can combine themselves into an unrepeatable perfection of a totally different kind. That’s what I’d love for you to experience.

I wrote this song on an instrument I’ve barely ever played before—a Russian instrument called a Domra. Maybe some Russians in the audience can verify that this is actually a Domra! It was given to me as a gift from my dad when I was young, before I even knew how to play guitar, and I never really figured out what to do with it. I got it out a few months ago, and it has a soft, gentle sound that made me want to play it for you guys.

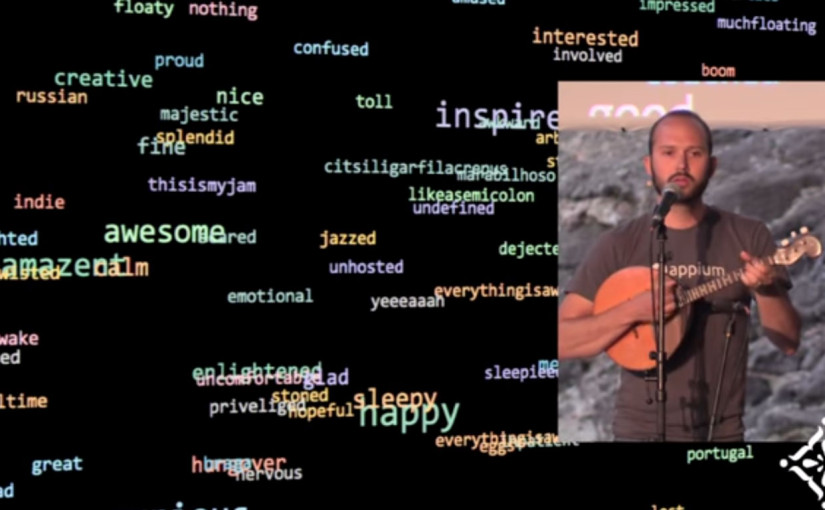

I’m going to do something a little different during this song. I’m putting a URL on the screen, and I’d love for you all to go there now on your laptops or on your mobile devices. It’s a mini app that asks you to enter one word that describes how you’re feeling (notice that it’s a text field and not a select box!). I thought we could try an experiment together, to make this experience even more unique. As I play the song, submit the words you’ve chosen, and the words will be animated on the screen up here in real time. You can update them in real time as well, so the words can change over the course of the song. I have two simple requests: first, please be honest. Second, please don’t be a troll. I know anonymity on the Internet almost guarantees someone will want to write something obscene, but I have higher expectations of this community. I’d love to have you experience this with me.

[Song, working title: Planned Obsolescence]

My eyes falter, drop their gaze

Doubt enfolds me in its hazeWhen will you come to me?

When will I know your name?

When will I feel that this is real?All I have are shreds of faith

These simulations I have madeI need a solid truth

Planted in solid ground

Something I can’t exchange forA newer model wrapped in a box

Planned obsolescence in my soul, soThere is life in our difference

Bringing out what I cannot know of myself

But the mountains have been laid low

And all Others are gone from experienceThere was a meaning here I swear

But I can’t see it any more

I’m just putting one last slide up with some resources you might want to take a look at if this topic interests you. A couple books I mentioned, as well as my blog, where I write about this stuff periodically. Also, the little Meteor app I created for the live experience is open-source, up on GitHub. Take a look!

Have a great rest of your conference everyone.

1 reply on “Internet of Nothings”

That was courageous and well-done, Jonathan, both the talk and the song.

Best regards, Albert